Ever looked at your backyard chickens pecking away and wondered what’s happening inside those feathery bodies? I certainly have! One of the most common questions chicken owners ask is about their digestive system – specifically how many stomachs does a chicken actually have?

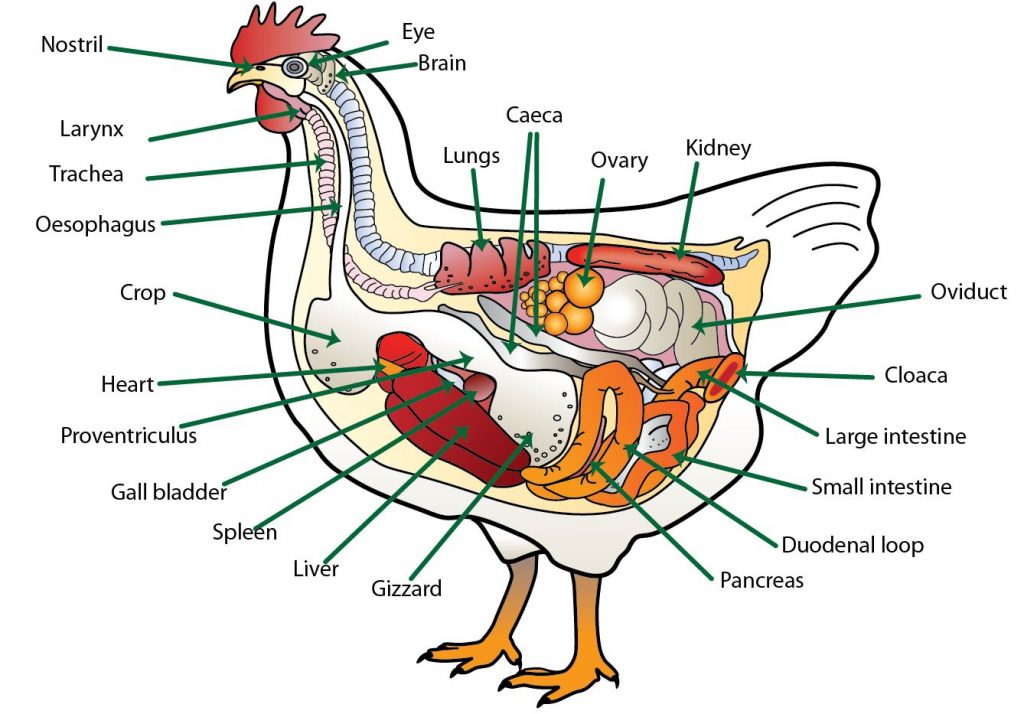

Let’s cut right to the chase: Chickens have one stomach with two distinct compartments – not multiple stomachs like cows. Their stomach consists of the proventriculus (the glandular stomach) and the ventriculus (commonly called the gizzard). This unique setup helps them process food without teeth!

The Truth About Chicken Stomachs

If you’ve been confused about chicken anatomy, you’re not alone. Many folks mistakenly believe chickens have multiple stomachs because their digestive system is so different from ours.

The proventriculus is where digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid are added to food, starting the chemical breakdown process Then the gizzard takes over as a muscular grinding organ that physically breaks down food – essentially doing the job our teeth would do

So while chickens technically have just one stomach with two compartments, their digestive system is fascinatingly efficient in its own right.

The Complete Chicken Digestive Journey

To truly understand how a chicken processes food, we need to follow the entire journey from beak to, well, the other end. Here’s what happens when a chicken eats:

-

Beak/Mouth: Chickens pick up food with their beaks. Since they have no teeth, they can’t chew! Their mouth contains salivary glands that add moisture and some initial enzymes like amylase to start digestion.

-

Esophagus: This flexible tube carries food from the mouth to the crop and then to the proventriculus.

-

Crop: Located in the neck region, the crop is an expandable pouch that stores food temporarily. You can often see it bulging after a chicken has eaten. It’s basically a holding area that allows chickens to eat quickly and digest later. When empty, it signals hunger to the brain.

-

Proventriculus This is the first compartment of the stomach where digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid begin breaking down food chemically

-

Gizzard (Ventriculus): The second stomach compartment with thick, muscular walls that grind food. Chickens often eat small stones that collect in the gizzard to help grind food – nature’s food processor!

-

Small Intestine: Divided into the duodenum and lower small intestine (jejunum and ileum), this is where most nutrient absorption happens. The pancreas and liver contribute digestive juices here.

-

Ceca: Two blind pouches that ferment remaining material and produce some B vitamins.

-

Large Intestine: Where final water absorption happens.

-

Cloaca: The exit point for digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems.

Why the Gizzard Is So Important

I can’t stress enough how cool the chicken gizzard is! Since chickens don’t have teeth, they rely on this muscular organ to mechanically break down food. When allowed to free-range, chickens naturally pick up small stones and pebbles that collect in the gizzard. These stones help grind up food into smaller particles.

The gizzard muscles are incredibly strong – they can crush nuts, seeds, and even small bones! If you’ve ever eaten gizzard, you’ve probably noticed how tough and muscular it is.

For pet chickens who don’t forage freely, providing grit (small stones) as a supplement is essential for proper digestion. Without it, they can’t properly grind their food.

Common Digestive Issues in Chickens

Understanding the chicken digestive system helps us spot when something’s wrong. Some common problems include:

-

Crop Impaction: When the crop becomes blocked or stuffed with material that won’t pass through. You might notice a swollen crop that doesn’t empty overnight.

-

Sour Crop: A yeast infection in the crop that gives it a sour smell.

-

Gizzard Damage: Sharp objects like tacks or staples can damage the gizzard due to its grinding action.

-

Necrotic Enteritis: Severe intestinal inflammation that can be fatal.

Comparison to Other Animals

Chickens have a monogastric digestive system (one stomach) like humans, dogs, and pigs, but with those unique adaptations I mentioned. This is different from ruminants like cows and sheep that truly have multiple stomach compartments (four, to be exact).

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Animal | Stomach Type | Number of Compartments |

|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Monogastric | 1 stomach with 2 compartments |

| Human | Monogastric | 1 |

| Cow | Ruminant | 4 (rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum) |

| Horse | Monogastric | 1 |

How Long Does Food Take to Digest?

One thing that amazes me about chickens is how quickly food can pass through their system. According to some studies, food can begin to appear in chicken poop as little as 3-4 hours after eating! However, this varies based on:

- The type of food eaten

- The individual chicken

- How full the crop was

- Environmental conditions

In some cases, food might stay in the crop for up to 24 hours before continuing through the digestive system.

Feeding Your Chickens for Optimal Digestion

Now that we know how a chicken’s digestive system works, we can make better feeding choices:

- Provide grit if your chickens don’t free-range or if they eat whole grains

- Offer probiotics to support healthy gut bacteria, especially for young chicks

- Ensure clean water is always available for proper digestion

- Include some fiber in their diet to keep things moving

- Avoid sudden feed changes that can upset their digestive balance

The Microbiome: An Important Player

Just like in humans, the chicken digestive tract contains beneficial microorganisms that aid digestion. These intestinal microflora help break down food and protect against harmful bacteria.

When chicks hatch, their digestive tracts are nearly sterile. In nature, they would get beneficial bacteria from their mother hen’s droppings. For incubator-hatched chicks, probiotics can help establish a healthy gut environment.

So, How Many Stomachs Does a Chicken Have?

To wrap it all up: chickens have ONE stomach with TWO compartments – the proventriculus and the gizzard. Together, these organs handle both the chemical and mechanical aspects of digestion that would otherwise require teeth.

The entire digestive system is a marvel of efficiency, allowing chickens to process a wide variety of foods from seeds and insects to kitchen scraps and commercial feed.

I’ve been raising chickens for years now, and I’m still fascinated by how their bodies work. Understanding their unique digestive system has helped me keep my flock healthier and recognize problems early.

For anyone raising backyard chickens, knowing the basics of their digestive anatomy isn’t just interesting trivia—it’s essential knowledge that will help you better care for your feathered friends!

FAQ About Chicken Digestion

Do chickens need teeth?

Nope! Their gizzard does all the grinding work that teeth would normally do.

What is chicken grit and do all chickens need it?

Grit refers to small stones that help the gizzard grind food. Chickens that eat commercial pellets only may not need supplemental grit, but those eating whole grains or foraging should have access to it.

Can chickens digest everything they eat?

Not everything. They’re omnivores with limitations. Some foods pass through undigested, and others (like certain plants) can be toxic.

Why do chickens peck at the ground so much?

They’re often looking for tiny stones for their gizzard, as well as searching for seeds, insects, and other food sources.

How often should chickens poop?

Healthy chickens poop frequently – sometimes dozens of times daily! The frequency, color, and consistency can tell you a lot about their digestive health.

Next time you watch your chickens happily pecking away in the yard, you’ll have a much better understanding of the amazing digestive journey that food is about to take! Their single stomach with its two specialized compartments is just one of the many fascinating adaptations that make chickens such unique and efficient creatures.

Mouth structure

Fowls don’t have lips and cheeks, they instead have a beak which is an area of dense and horny skin lying over the mandible and incisive bones that serve as the bony foundation. There are no teeth. The so called egg tooth found on the end of the beak of newly hatched chickens is an aid to their escape from the egg at hatching and disappears after a day or two. The hard palate that forms the roof of the mouth, presents a long, narrow median (median – along the middle) slit that communicates with the nasal cavity. The hard palate has five transverse rows of backwardly pointing, hard, conical papillae. Numerous ducts of the salivary glands pierce the hard palate to release their secretions into the mouth cavity.

Enzyme action

After ingestion, the food is mixed with saliva and mucous from the mouth and oesophagus and these secretions thoroughly moisten the food. The enzyme amylase, which is produced by the salivary and oesophageal glands and found in the saliva and mucous, can now commence to breakdown the complex carbohydrates. However, the amount of enzyme action at this stage is minimal and the first major enzyme activity takes place in the proventriculus and in the gizzard.